Den Stygge Stesøsteren, dir. Emilie Blichfeldt

Trigger warning: this review will refer obliquely to fairly intense body horror.

What if Cinderella's 'ugly' stepsister actually became beautiful after being subjected to painful plastic surgery and dubious slimming treatments, but at devastating cost to her mental and physical well-being?

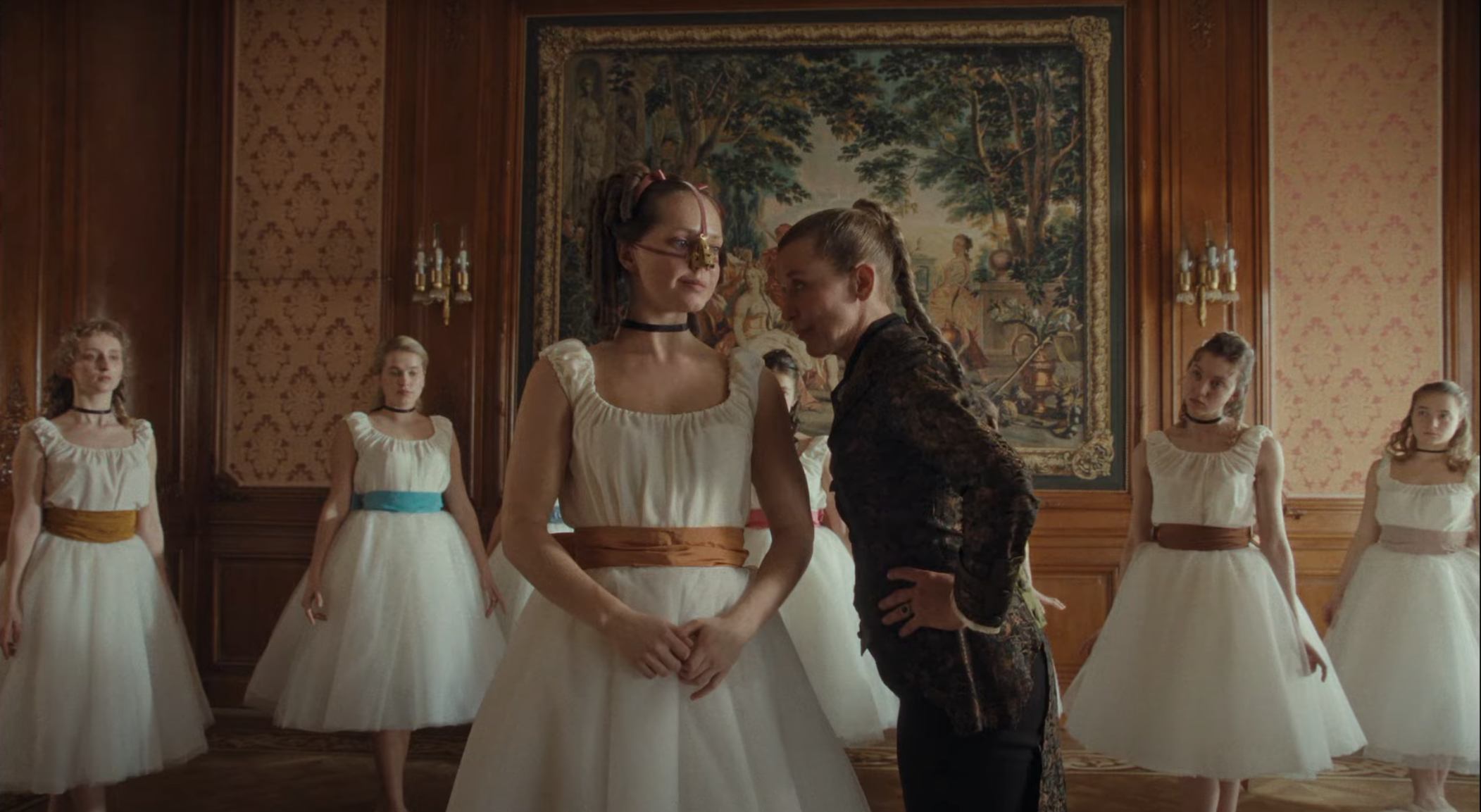

Emilie Blichfeldt sets out to answer this question in her feature-length directorial debut The Ugly Stepsister, wielding 1970s camp along with flinchingly brutal body horror to recast the Cinderella story as a critique of maternal figures who perpetuate patriarchy, to the harm of those under their care.

Lea Myren (who is by no means ugly) plays the titular character Elvira with an almost cartoonish but heart-winning naïveté and innocence, while Thea Sofie Loch Næss gives Cinderella a (narratively justified) Mean Girls-esque haughty bitchiness. The traditional protagonist/antagonist roles are muddied here successfully so this retelling feels fresh.

Elvira is doomed from the start: we first encounter her breathlessly reading the Prince's slim volume of love poetry (think sadboi in rhyming couplets, which, according to Blichfleldt, were conceived as a love child of John Donne and her own deliberately bad poetry.), which fuel fantasy sequences of Happily Ever After with him. These sequences are set to pulsing New Wave synths, and feel like an ABBA music video from the seventies. I am fond of these anachronistic soundtrack choices that underscore the artifice of what the audience is watching.

And as in the fairy tale, the plot kicks off when the Prince announces a ball in four months' time where he will pick, from all the jungfrau invited, his bride. Elvira's descent as she is being prepared for this ball is truly harrowing. Her mother sends her for nose jobs sans anaesthetic (by a quack plastic surgeon whose clinic's motto is Beauty is Pain).

She is enrolled into a finishing school, where she is subjected to verbal abuse by the dance teacher. The principal slips her a tapeworm egg to hasten her weight loss (after all, this is almost 3 centuries before we'll get Wegovy)... and I'll leave you to imagine the consequences. All through this, Elvira never stops reciting the Prince's poetry to herself, her sister, and her stepsister Cinderella.

The body horror here hits harder than The Substance. (I tend to think I have a fairly high tolerance for this stuff, which isn't to say I don't flinch or wince.) Stylistically, these sequences have a grounded realism, coupled with unvarnished screaming, that made me feel I was watching a forbidden snuff film. A sequence mid-film involving false eyelashes and needles had me seriously considering walking out of the cinema. And the penultimate and final acts (which hews close to the popular fairy tale ending) include some of the darkest humour you'll ever encounter: absurd and ridiculous and thoroughly uncomfortable to watch.

If you haven't subscribed to this newsletter, why wait? For a small sum, you can help me talk about film and cinema!

And while the gore will undoubtedly catapult this film into cult classic, it's Blichfleldt's depiction of the female gaze that also merit discussion and attention. The nudity and sex is seen solely through the eyes of teenage girls: captured in soft focus with ethereal synth playing (Blichfleldt has tipped her hat to Polish erotic films from the 70s), buttocks and phalluses charged with a chaste eroticism, forbidden and yet inevitable.

This genre bending debut – this is after all a period body horror satire – bodes well for Blichfeldt: I don't believe she will be pigeonholed for her next film, which I will await eagerly for.

Member discussion